Another school year had begun.

Just as they always ended with exams, they started with choosing classes. Only this time, the stake was higher than ever. On top of picking classes for the coming year at Hurtwood, we also needed to decide which subject we were going to study at university—the university application process started straight away with the new term.

Thinking about what to study in university, when I was only half way through high school, was somewhat strange to me. In China, the university application process was a non-event. It was an almost automatic process happened only after graduation. All that was needed was the result from the national graduation exam. Those who achieved the highest marks could go to Peking or Tsinghua University—China’s Oxbridge equivalent; those who did marginally worse could go to the next tier and so on and so forth. Somehow, there were even a clear hierarchy in terms of which subjects one should study based on grades as well. Those with higher marks would go for the more quantitative subjects while those with lower marks would go for softer subjects. Things like preference and interests, on the other hand, rarely mattered.

There was a catch of course: being the only input into the process, the pressure on getting a good exam result was immense. One mark would often mean the difference between being accepted or rejected by a dream university. The Communism value of everyone getting the same result was nowhere to be seen in this process. Instead, people fought tooth and nail for each and every mark so that one could stand out from the rest.

To make sure there would be enough differentiation amongst the tens of millions of high school graduates every year, the exams were set to be impossibly hard. It was joked the day one took her high school graduation exam was the peak of her intellectual ability and knowledge level. Given most Chinese parents had given up tutoring their children personally by this stage—the material was too difficult, the joke might even be true.

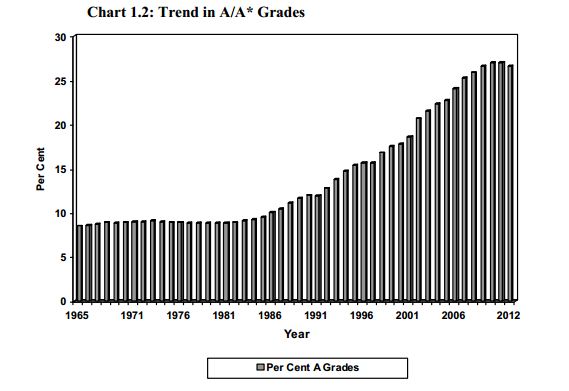

In contrast, I was glad to see the Communism spirit was still well alive in the UK. Instead of getting individual exam marks, students were grouped into several grade bands. Those who got above 80 were issued an “A”, for example, whether it was 80 or 100. One point or even a ten points difference didn’t really matter. It was still the same grade. What is more, the proportion of students who got high grades like A and B also increased steadily over time. Not all students were A students yet, but it seemed eventually we would get there. This was where Karl Marx chose to live after all.

Today, Dennis and I sat down to start working on our university application forms. As we both put down “A” in our first year Economics results, we both felt quite happy. It was the highest grade which gave us a good chance getting into the top universities. But I was sure I was the happier one out of the two. Dennis’ A was a 97-mark A while mine was a 80-mark A. Long live letter grades and equality.